Just what is a coywolf, anyway? Simply put, it’s some combination of western coyote and eastern wolf with a bit of dog DNA thrown in.

Unlike grey wolves, the smaller eastern wolf and coyotes evolved in North America, so share some genetic material from thousands of years ago.

But, in the early 1900s, settlers almost wiped the eastern wolf out. That allowed western coyotes to migrate eastward where they eventually began mating with eastern wolves. The result is the coywolf, also known as the eastern coyote.

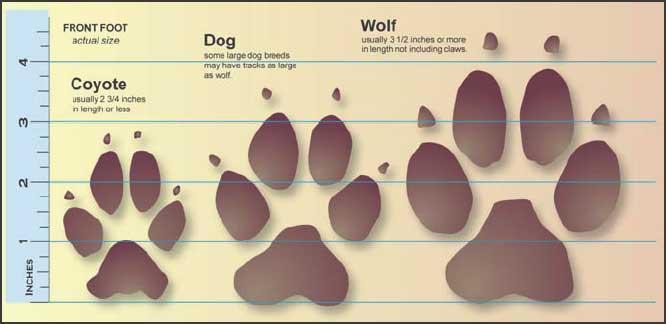

These hybrids generally have longer legs than coyotes, plus bigger paws and a broader skull, which provides space for bigger teeth and a stronger jaw. Like wolves, they sometimes hunt in packs and take down larger prey than coyotes normally do.

Coywolves may get their size and strength from wolves, but they often retain the mindset of a coyote. This is most apparent in their comfort level around humans. In fact, some are conducting their everyday lives in densely populated areas such as Toronto, Montréal, Boston, Chicago and New York.

Most people never see these animals or have any idea they’re present. That’s because urban coywolves are usually on the small side and tend to be totally nocturnal.

No one’s sure how the relationship between humans and coywolves will evolve. They scavenge human garbage, sneak up on porches to eat pet food left outside and kill pets. And, although rare, they have acted aggressive towards people.

In Nova Scotia’s Cape Breton Highlands National Park, coywolves (officially called eastern coyotes in the park) have followed people and chased cyclists, biting the rear tires of bikes as if trying to take down prey. In October 2009, nineteen-year-old singer-songwriter Taylor Mitchell was mauled to death by coywolves while on the park’s Skyline Trail.

Incidents outside the park include coywolves attacking dogs, trailing people and, on at least two instances, attacking them. All coywolf/eastern coyote attacks have been linked to habituation and possibly being fed by humans.

Photo by Jonathan G. Way