Sometime in October I got scooped up in a social whirl that kept me going from birthday parties to concerts, dinner’s out and more day after day. That ended in mid-December when I headed south to spend two weeks celebrating the holidays with family.

So much fun! So much good food! And it was wonderful to spend time with family and friends! But, of course, the busier I got, the less time I had for writing. Each week I thought that would change but it didn’t. By the time I flew home on the last day of 2025, I was ready to get back to work.

The last leg of my journey was delayed for hours due to a thick shroud of fog draped over Vancouver Island. When the plane finally touched down in Comox, I was giddy with relief. I just wanted to get home and back to “my real life.”

The cab dropped me off at 12:10 a.m. on New Year’s Day. As I stepped into the near blackout of my front door, I felt something substantial, yet squishy, under my feet. My immediate thought was dead animal.

I fumbled for the small flashlight I’d attached to my keyring. I didn’t find it but did manage to open the car trunk and activate the car alarm. Looking around at all the dark windows in my complex, I giggled and called out “Happy New Year!”

When I finally got inside and was able to shed some light on the matter, the dead animal turned out to be a large wreath someone had left on my doorstop. What a relief!

I love the New Year and the opportunity it offers for big dreams and introspection. I usually spend about an hour plotting out what I want to accomplish in the upcoming months.

I fully intended to do that when I woke up the first morning of 2026. But both my body and brains said no. I was tired, so decided to wait a day before dashing off a list of projects.

The next day’s repeat rebellion of body and brain made me realize my energy bank was empty. I decided to give myself a couple of days to recover…which stretched into a week!

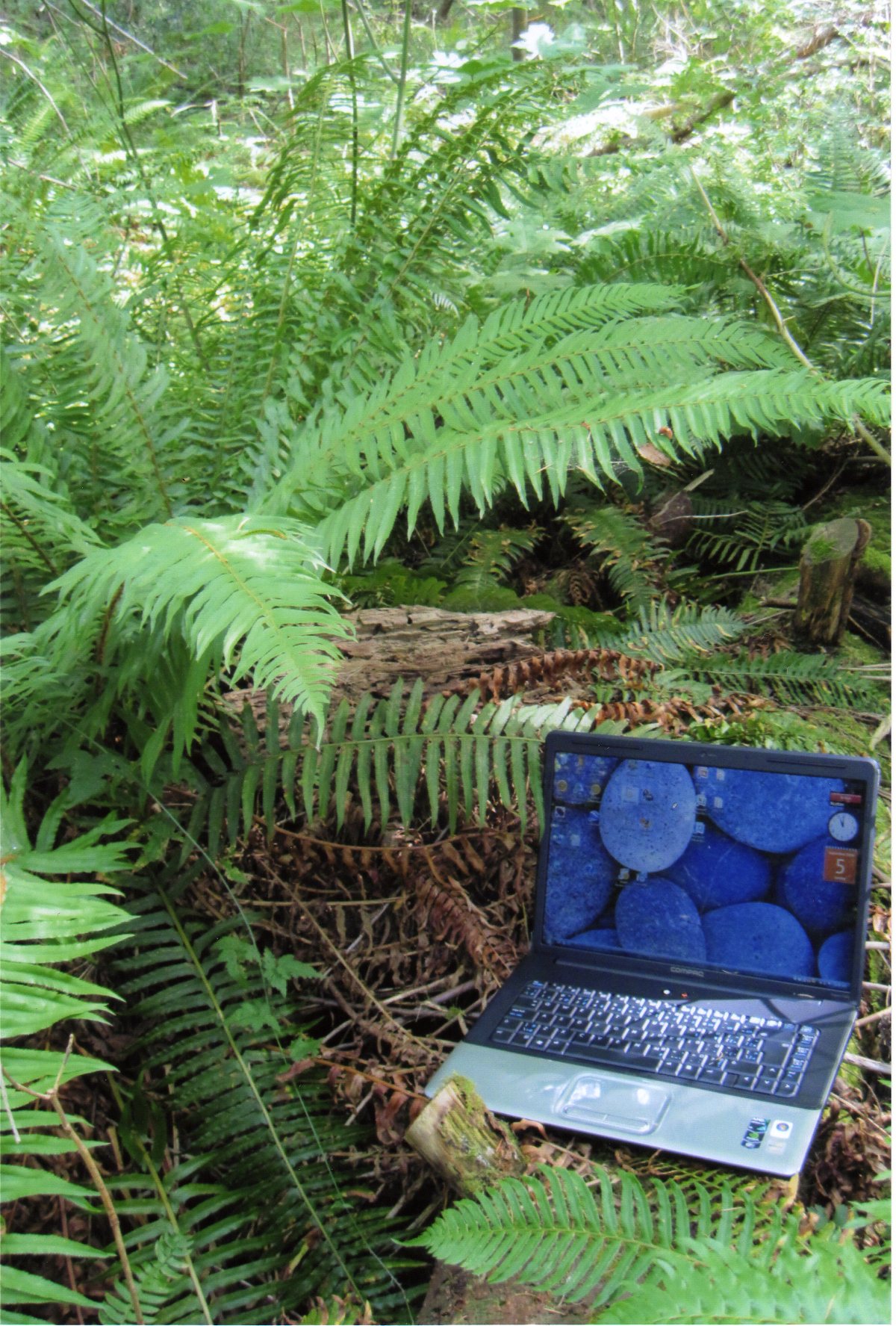

I ate and slept when I wanted, puttered, went for solitary walks in the woods and, aside from a few short emails and texts, communicated with no one. I was surprised to find it not boring but relaxing.

When I did sit down to formalize what I want to accomplish this year, I spent a few minutes considering what gave me energy in 2025 and what drained it.

The answers were obvious: energy and joy came from writing, tai chi, music, and spending time in nature and with family and friends. The drains: too many appointments and too much socializing.

I love having fun with friends and family but, as a writer — and introvert — I also need alone time. I added “fix the teetertotter” to my 2026 list. I’m not cutting out any social activities out, just making sure there’s more balance.

need alone time. I added “fix the teetertotter” to my 2026 list. I’m not cutting out any social activities out, just making sure there’s more balance.

And you know what? I found my mini-retreat so beneficial, I added it to the list too.

Top photo by Rick James

Bottom photo by Dodie Eyer

read a story or two before I closed my eyes on the day gone by. It didn’t matter if the reader was my mom or dad, one of my grandparents, an aunt, or even a babysitter. I eagerly looked forward to being immersed in another realm and the excitement of turning the page to discover what came next.

read a story or two before I closed my eyes on the day gone by. It didn’t matter if the reader was my mom or dad, one of my grandparents, an aunt, or even a babysitter. I eagerly looked forward to being immersed in another realm and the excitement of turning the page to discover what came next.

My editing takes place in a variety of ways. I usually begin reviewing the text on my computer, then shift to hard copy as the eye picks up different glitches in different mediums. Reading the story aloud is another way to make sure every sentence is up to par and creates a cohesive, dynamic whole.

My editing takes place in a variety of ways. I usually begin reviewing the text on my computer, then shift to hard copy as the eye picks up different glitches in different mediums. Reading the story aloud is another way to make sure every sentence is up to par and creates a cohesive, dynamic whole.

For several years I had been fulfilling my childhood dream of being a writer and had moderate success publishing articles in magazines and newspapers. But I was itching for something more. Something big and challenging to focus on.

For several years I had been fulfilling my childhood dream of being a writer and had moderate success publishing articles in magazines and newspapers. But I was itching for something more. Something big and challenging to focus on.